Looking = Loving

Probably the strangest object in my house growing up was my mother's "pet rock". It was literally a small, smooth rock with a face painted on it, but my mother insisted that we treat it as a sentient creature named Jemima. She loved to show off all the tricks it could do. These tricks included "sit", "stay", "play dead" and, with some encouragement, "roll-over". She would boast about how it was the most well-behaved pet in the household. My mom thought this was hilarious, and obviously we thought she was nuts.

Pet rocks were a big craze in the 1970s. Some guy named Gary Dahl sold a million of them for $4 a pop, along with an honestly hilarious guide to the "care and training of your pet rock". This is what bored teenagers did in the 70s instead of TikTok, and I take it as proof that human beings can bond with anything that has a face.

It's one of my favourite things about humans, actually: how we can form attachments to the weirdest things.

I've been stuck in my house a lot, very far away from my loved ones. And I've been finding myself getting weirdly sentimental about strange things recently, like all of the energy I usually put into loving my friends and family is attaching itself to any old thing it comes across. I've found myself feeling pangs of affection for pigeons, obsessing over the territory battles going on between the baby spiders in my bathroom, spending long minutes marvelling at the shape of the tree I can see through the window above my desk. Falling in love with the world.

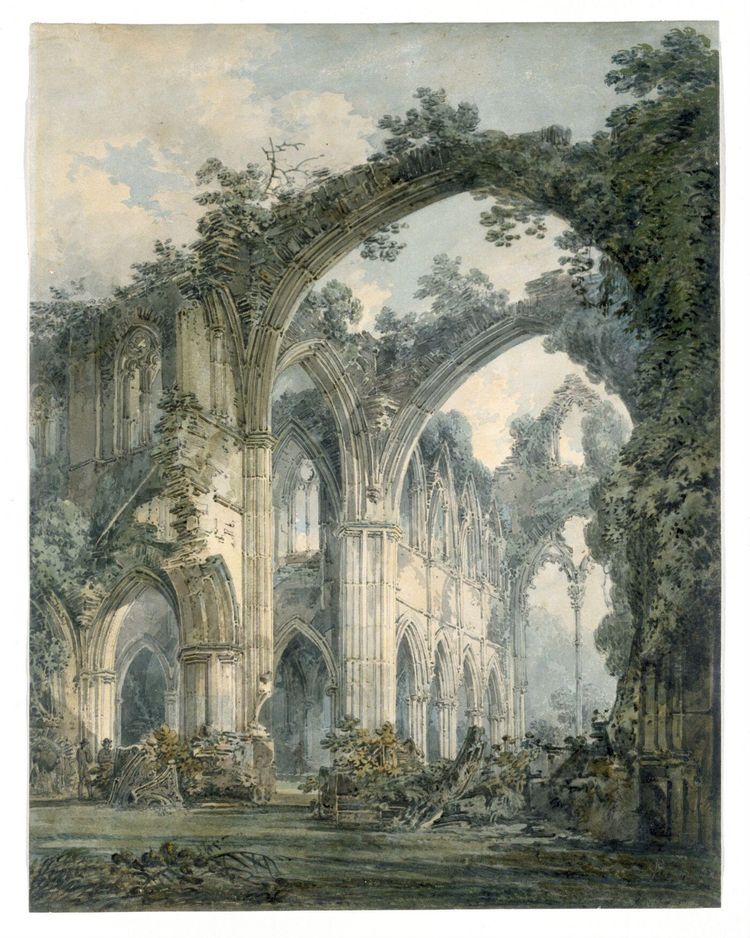

In my observational drawing classes, we're studying 17th-19th century naturalists: those early pioneers of European "natural history" who explored and documented the natural world. They believed in close observation of individuals within their environment, and were interested in charting the evolution of species.

This led to a boom in naturalists running around in various countrysides assembling vast collections of things, like shells or insects or wildflowers. These collections were displayed in private homes, and eventually became the foundations of the world's natural history museums, like the Iziko in Cape Town or the Natural History Museum in New York, or my absolute favourite museum in the world, the Hunterian Museum in London (fair warning: my friend Simon calls it the "dead baby museum", and he's not wrong - it's an unsettling place).

Sidenote: a lot of this urge to categorise and classify within rigid hierarchical systems led to some profoundly problematic shit, like the development of totally nonsense racial science. Natural history exploration was tied up with colonialism, and often missed an awareness of the interconnectedness of organisms that was better understood by the very cultures they were in the process of destroying. There was a real dark side to all this, and it wasn't only cute nerds innocently collecting insects. But I digress.

These were the days before colour photography, so art and science were deeply entwined; drawing something accurately was the only way to document it. But drawing does something else, too: it forces you to slow down and really look at something.

It was this strange time when science was becoming professionalized, and there were walls going up between Official Scientists who were allowed to Do Science Officially (attached to scientific academies) and everyone else. But those borders were still porous, and a lot of naturalists were passionate amateurs, rather than professionals.

A lot of the greatest naturalists were women, like Marriane North, Else Bostelmann, Margaret Gatty and Maria Sybilla Merian. Even Beatrix Potter, the creator of both The Tale of Peter Rabbit and my lifelong fear of owls, was a naturalist. Before she got into terrorising/entertaining children, she studied mushrooms. Fun story: in 1897, she made a pretty major breakthrough about the germination of mushroom spores and submitted a paper about it to one of the fancy science academies (the Linnean Society). They accepted her paper, but wouldn't allow HER into the academy when they presented and debated it (since, you know, woman).

The Linnean society did ultimately write her a letter of apology ... in the year 1997, 54 years after she died. NICE GOING, SCIENCE DUDES.

Here's what I love about these old-timey naturalists: they weren't professionals. They were people who fell in love with the world, and thought it was so beautiful and strange that they devoted their lives to looking at it.

In fact, a lot of them were what was known as "parson-naturalists", priests who saw studying the natural world an extension of their worship of God. That was how Darwin got started, actually: he studied to be a priest, but ultimately found that he was more strongly drawn towards "natural philosophy" than abstract theology.

We've never needed people to fall in love with the natural world as much as we do today. Global populations of mammals, birds, fish, amphibians and reptiles plunged by 68%, on average, between 1970 and 2016. We know, intellectually, that's bad. But we don't feel anything when we look at that number. Our brains aren't designed to connect with numbers in the way that they connect with faces, even faces we made by putting googly eyes on clumps of moss.

I watched a documentary on Netflix a few months ago called David Attenborough: A Life on Our Planet. It's a devastating, brilliant piece about the damage humans have done to the planet over the past century. But it's not the facts that get to you; it's seeing for yourself what the damage looks like. There's this one scene showing a rainforest in Borneo that was cleared to be replaced with palm oil plantations (which has happened to over half of the world's rainforests). It closes with a shot of a newly homeless orangutan climbing a lone tree, and I swear, if you can watch that scene without balling your bloody eyes out then you are made of titanium.

Art like that puts a face onto biodiversity loss. It tugs on our sweet human heartstrings, way more than reading facts about it can do.

I read a dozen books about climate change last year, and my favourite by far was Naomi Klein's This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate. There's a chapter called "Love Will Save This Place" where she talks about examples where passionate communities successfully pushed back against new fossil fuel projects. These communities were motivated by concerns about air and water pollution, but also by love for the natural world they are connected to.

The power of this ferocious love is what resource companies and their advocates in government inevitably underestimate, precisely because no amount of money can extinguish it. When what is being fought for is an identity, a culture, a beloved place that people are determined to pass onto their grandchildren, and that their ancestors may have paid for with great sacrifice, there is nothing companies can offer as a bargaining chip. No safety pledge will assuage; no bribe will be big enough. And though this kind of connection to place is surely strongest in Indigenous communities where the ties to the land go back thousands of years, it is in fact [the grassroots climate justice movement's] defining feature.

Part of what has gone wrong with the human species' relationship with our world is that we've treated it as a resource to be accounted for only in how it can be of utility to us, rather than as something that is precious for its own sake. We've treated the finite as though it is infinite, and extracted without restoring over several centuries. Falling in love with nature, as unbearably hokey as that sounds, is the only thing that can break us out of this mindset. As Iris Murdoch puts it, "love is the difficult realisation that something other than yourself is real."

There are still ways to contribute meaningfully to science as an amateur, even today. Now, we call this "Citizen Science" (although you're welcome to call yourself a Naturalist if you prefer). There's this puzzle game you can play on the web that helps scientists figure out how proteins fold (a project that might help us design better drugs to treat HIV). Or you can help scientists label images of Beluga Whales to learn more about their family structures. Zooniverse has dozens of Citizen Science projects, including things you can do in your garden, in nature, or online.

If you're in South Africa, and thrilled that the beaches have re-opened, why not join the Elasmobranch Monitoring Organization (ELMO) which tracks shark, ray and skate populations. You can help by submitting photos of eggcases that you find on the beach.

I'm just leaning into my weirdly intense feelings about nature. I've been drawing lichens (CRAZY FACT about lichens: they're not a single organism, but actually a whole colony of different algaes and fungi working together - magical, right?!). I've started my own tiny collection of mollusk shells. I've been seriously debating buying a microscope. The other day, I discovered that you can boil red cabbage and then test pH levels with the liquid, so I've been running pointless science experiments in my kitchen for my own amusement.

Yes, I'm still in lockdown, and maybe, like I judged my mother and her pet rock, I've just gone slightly mad. But heck, it's the Winter of Weird and I'm just going with it. The world is bloody beautiful, and it's a joy to look at it.

I'll leave you with some words by Rachel Carson:

I believe that the more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe around us, the less taste we shall have for their destruction.

Tell me about your weird and marvellous nature collections, friends!

Wishing you love, wonder and pet rocks,

Sam

Updates from Sam-Land

- Ray Mahlaka from the Daily Maverick hosted me on a webinar about personal finance on Wednesday, and you can watch the whole thing here.

- If you have a retirement fund, pension or other investments in South Africa, your money is probably being used to prop up fossil fuel companies. If you hate this, sign onto this open letter demanding SA's major asset managers offer fossil-fuel free alternatives: fossilfreesa.org.za/our-campaigns-…

- Diiiiiiiid I mention that I finished a draft of my novel? Did I?

Member discussion